This past spring I published my first book, a novel called The Sky Was Ours that took me more than a decade to finish. For a few more weeks, as I finish out a run of events and promotion, I’ll be too busy to face any larger existential questions about next steps. But I can already sense what’s coming after: stillness. Suddenly, it’s going to be very, very quiet. And then — I’m bracing myself for it already — I’m going to have to make some tough decisions about what to do with the next phase of my life.

I don’t mean stillness in a global sense. Certainly, our surrounding moment is the opposite of peaceful — each day, new horrors mount in the news. In my day-to-day work as a climate journalist, it’s my job to confront specifically environmental forms of damage, exploitation, and injustice, an urgent and often sorrowful beat during this era of rapid warming and widespread inaction. But with a major project soon to be behind me, I’ll have more time to reflect on how best to use my energies as a writer and storyteller. Our urgent moment stands uncomfortably at odds with quiet contemplation, and I’ll have to ask myself how best to push this inner stillness toward action.

For years, I was able to hold that kind of decision-making at bay. I was working on a book I believed in, and its position in my life was non-negotiable. I’d gone to grad school to learn to write fiction. My friends and family expected the book; so did my agent. Most of all, I’d committed as an artist: I’d stumbled into a project that felt necessary, and I promised myself I’d see it through. Even on the weeks when the work was difficult, when I felt at an impasse with the book, when I was no longer sure what form the story should take, I understood my job was to find a way forward. I did have a few dark nights of the soul, where I despaired at ever finding an adequate approach. For the most part, though, I silenced my doubts through the doing. I had faith that the answers I wanted were in the work itself, and for the most part, I eventually found them.

What I didn’t realize at the time, what I’m only starting to see now, is that my doggedness came with a drawback: the single-minded focus that was so important to me as an artist also kept certain existential questions at bay. Now that I’m in between projects, without The Sky Was Ours claiming my time and attention, I suddenly find myself wondering how to fill the book-shaped hole in my life.

Conviction is a beautiful thing. If we are the fire, it is the fuel. It’s what allows us to set big, abstract, overwhelming goals and push toward them day after day, even when we have no assurance that our work will ever be sufficient, ever be complete. Writing a novel is like that. So is any other worthwhile pursuit — advocating for justice, building an institution, caring for the people you love. When desired outcomes are uncertain, conviction is what powers us through.

But as I enter this in-between period — a state we might call liminal, in the sense of being positioned at a threshold — I am trying to value its awkwardness, its ungainliness, its uncertainty. Though I valued the conviction I had about my work, I am now trying to value its absence. Yes, it can be good and healthy to push whole-heartedly toward our goals, to free ourselves from constant second-guessing. But maybe we also need intervals in which to take nothing for granted. To pause and reflect and wonder. To ask ourselves more open-ended questions and follow them wherever they might lead.

I am trying to be open to those questions now. Some of them are more pragmatic. What should the next book be? What new topic am I willing to spend years of my life pursuing? Should it be fiction, or nonfiction? I want my writing to rise to the urgent occasion of our moment, but which of the topics I know best deserves priority? Choosing a new project is a way of saying this matters most, and suddenly I don’t feel comfortable taking such an unequivocal stand. It was easier when the decision had already been made by a past version of myself, the person who started the project years ago that I inherited today.

But if I’m honest, this in-between period has raised more fundamentally unsettling questions. Like: Is writing the best use of the time I have left? Or has the time come to rethink the paradigm I’ve relied on for so long? I just turned 40 last month — in another 40 years, if I’m lucky enough to have them, what do I want to look back on? What do I want to know I tried my best to do? I always thought I wanted to mark my time in books, but I am using this in-between moment to think outside the paradigm, to question what I always thought I thought.

It’s an uncomfortable exercise. I’ve wanted to be a writer since I was a kid. I love literature deeply, and I’ve long believed in its power to bring out the best in us. Though it can be tempting to think of literature as an exercise that plays out from an ivory tower, I’ve written in the past about the value of writing even in — maybe especially in — troubled times. But I don’t want to take that belief for granted. I want to interrogate it. There is a kind of reflection that only becomes possible in the in between, when after so long, suddenly, everything is once again up for grabs.

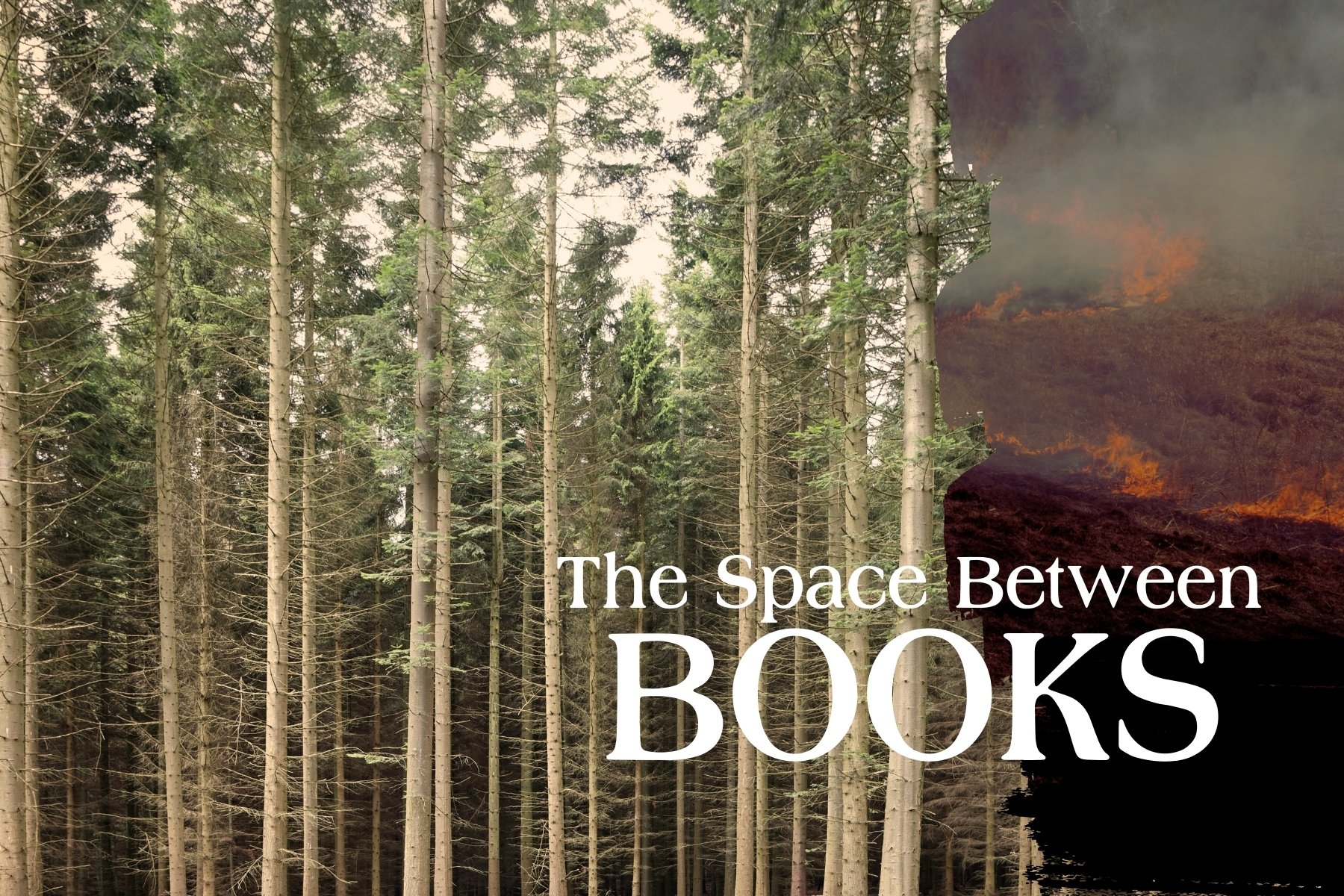

I have been thinking about fire. I spoke recently with a North Fork Mono tribal leader who described how First Nations people continue to use fire as a tool, in keeping with ancestral practice — clearing away overgrown forest, stripping away the plant species whose dominance squeezes out other life. Fire used this way is not a destructive force, but a cleansing one. Ashes nurture the soil; flames prepare the forest floor for new roots, new shoots. In the right hands, a fire does not really mark the end of something. It is the glorious force of in-betweenness, opening a bright door to the new.

We tend to think of conviction as our inner fire, and we can feel a temporary loss of conviction when that fire runs its course. But rather than lament the dimming of that blaze, maybe we should remember what fire leaves behind: emerging possibilities, springingly freshly into life. That regrowth today becomes tomorrow’s fuel.

The conception of inner fire as a single torch overlooks the cyclical nature of inspiration and creative effort. It is not only a solitary, burning flame. It’s also a force that clears the way, making room again for us to question our priorities and renew our values. It’s how we free ourselves from the thickly branched underbrush we’ve spent so long inhabiting. We burn, we let the sun in again, we see what else will grow.