I spent the day before my apartment flooded at home. At ease. Cozy on my couch as the rain fell. Letting my aching legs rest and my hopeful heart beat.

The day before I had hiked Mount Mansfield with a friend from out of town who was raring to do the 9 mile, technically challenging climb despite the heat and humidity. I knew I wasn’t in the best physical shape or mental state when we rolled up to the trailhead, but I was determined to power through, hoping the extreme effort and undeniably gorgeous views might push me out of the funk I’d been in.

It didn’t. It was just hard. As we hurried down the mountain, trying to outpace the ominous clouds and rumbles of thunder moving toward us, my legs were shaking. I wasn’t worried about getting rained on – that’s to be expected on a long hike. But I was sort of disappointed. I couldn’t access the feelings of pride or accomplishment that pushing myself usually offers in return. I was just exhausted.

Still, I imagined I’d do it again – and maybe do it better – because Mount Mansfield was basically in my backyard and would be for a while. Not a week earlier, my partner Gehrig and I had decided that we were going to stay in Johnson, where we’d rented an apartment for nearly a year. The two of us have moved around a lot – seeking newness and a place to belong to. California delivered on the adventure but it wasn’t home. So we headed back east, choosing Vermont because it is beautiful, familiar, and “climate resilient.” A lot of my job at Sterling College can be done remotely, but I needed and wanted to be on campus some of the time. But Gehrig is a musician, so being closer to a city makes things professionally easier for him. Johnson was a reasonable compromise. A midway point between Burlington and Northeast Kingdom. But like most compromises, it left us wanting. It wasn’t easy to make friends as the new folks in a small town. Winter driving was long and slick. And though we’d tried to invite people we met at shows to hang out, the hour drive to our place was an understandable deterrent. So we’d started touring apartments in Winooski, in St. Albans. We were all ready to sign a new lease when we realized that we might be “pulling a geographic” again.

Someone recently told me that it takes 5 years to really be settled. Having never stayed put that long – even as a child – I can’t say whether that’s true. But it did take 2.5 years to make a great group of friends in Davis, California – a group of friends we up and left just 6 months later as we felt pulled back East. As we toyed with moving again, we were uncommonly honest with ourselves and each other. We admitted that whenever we struggle to feel settled, feel at home, and find community, we mix it up. We leave. We flee back to the friends we already know, aware that they have busy lives and we probably won’t see them much anyway. In the soft light of candor, we realized that Johnson was an idyllic little community that we had not yet made enough of an effort to join. Despite the seclusion, the dirty house, the slanted floors, our rental was cozy, beautiful and ours. We felt fortunate to have a landlord that cared about us and treated us like real people in a real home. We decided to stay one more year, save some money, and really soak it in. Really love the place and the people around us. Once we made this choice, everything we had felt more cherished: the mountains around us, the garden plot we started, the quiet evenings and view of the milky way, the fire pit, and the budding friendships we’d allow to grow around it. The imperfections and inconveniences of life in Johnson – writing paper checks for the rent, having to walk to the PO box for mail, having just one coffee shop and small, spendy grocery store – started to feel quaint. And since I’d just chosen to reduce my hours at work, I felt like I could actually find the time to root in. To be the small town girl of my own fantasies – the one who crafts with neighbors and actually hikes the hills around her home.

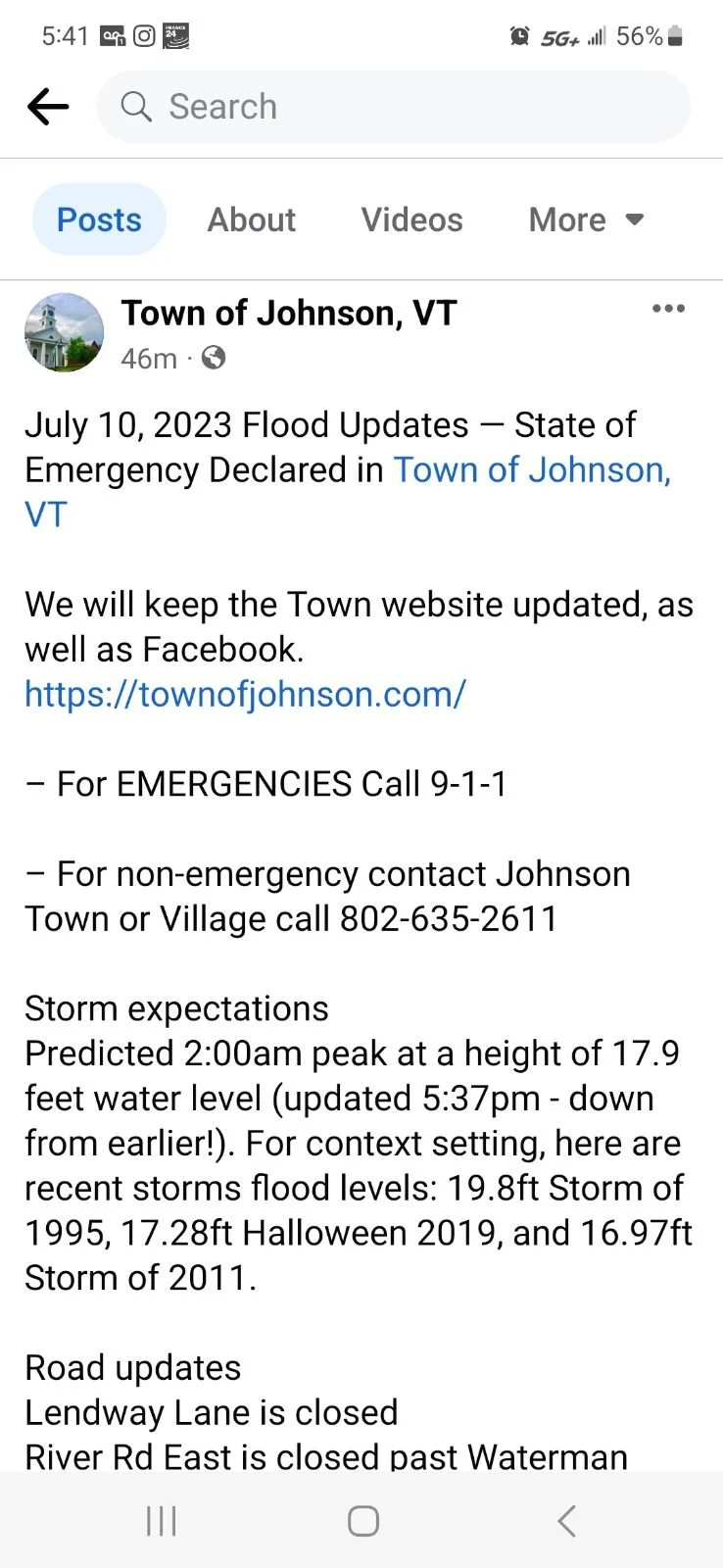

As I passed the quiet hours of July 10 by listening to the rain drum on the windows, occasionally my phone would chime with messages from friends from in and out of the state asking how I was doing with the flooding. What flooding? It was barely raining. I was cozy and dry.

There was a flood warning on my weather app but it simply said “don’t drive through water, it can whisk you away.” Check. I wasn’t planning on going anywhere. Playing it safe.

Front Porch Forum offered “free sandbags.” “Huh, for what?” I wondered. My landlord texted me a warning about how high the water would be. It was interesting but context-less information. Having lived there only a year, we had no frame of reference for how bad it might get. (I suppose this is a risk of being a transplant.)

My friend headed back to New Hampshire that afternoon and as we hugged goodbye, I told her to watch out for water in the roads and let me know when she made it back. Because Gehrig was out of town for the month, the rest of the evening was mine and mine alone. So I heated up a frozen dinner, and watched TV all evening. Chill.

A little before midnight, I decided to go to bed. I quickly fell asleep, but woke up less than two hours later suddenly aware of odd sounds.

An alarm nearby.

Water flowing.

People talking outside.

I peered outside my bedroom and saw water pooling in the parking lot behind my house. Water where it shouldn’t be was disorienting but not scary. Maybe because I was still partially asleep, I only felt curious. I moved from window to open window, snapping pictures. Neighbors were out in the street ogling the high water. But no one seemed afraid. It had the air of a snow day. Fun and weird weather – more spectacle than threat. People were calling out the latest weather updates with practiced assurance: “Nothing to worry about here. The river is supposed to crest at 2am. It won’t get much worse. We aren’t in any danger.”

Despite my neighbors’ ease, I had a quiet, creeping sense that I was missing something. I decided to move my car up the street. Just to be safe. A quick conversation with someone who was also parked in the dry lot in front of my house made me believe it was worth the small effort. The one thing I knew for sure was that cars and floodwaters do not mix. I knew not to drive through it, so I avoided the street to the left, which was already covered in water and tucked my Subaru Impreza a few houses down. This left me feeling very proactive and responsible – much smarter than the car owners who left their vehicles where water was already pooling around their tires. I felt a little dumb for having gone to bed before. This act was redeeming.

2 am came and went. The water was rising – imperceptibly. There was no rain.

The images of the street became gradually more eerie. Houses illuminated by street lamps were perfectly reflected into the still mirror that was once a dry road. I decided to get artsy with it. I waded into the knee-high water and snapped picture after picture. Marveling at the strange beauty.

Even as I failed to notice the rate the water was rising, the scenes became weirder. The yard now had a current. Car alarms were sounding in the distance. Fire trucks driving through the water created huge wakes. Sitting on the dock that was once my front porch, I was literally splashed with a moment of clarity at the severity of the situation when the waves created by the passing truck sent a ripple of water over my head, drenching my pajamas. The toilet and tub began uttering foreboding, ominous gurgles.

A gorgeous way for things to be all together wrong. And yet the water was still several feet away from the house. Further from the doors, further still from the windows. I didn’t hear neighbors panicking. Or even responding.

At 3:25, the amorphous reflections of light that dance at the bottom of a clear pool were instead glinting off my bedroom ceiling. It was hard not to be distracted by the disorienting beauty. It still had not occurred to me that I was in danger or that I should prepare. Prepare for what, and how? My main concern was getting back to bed soon, so I could be rested for work the next day.

And then things shifted: Neighbors that had been wading around the street suddenly had to be picked up by boat as the water continued to rise and the current got stronger. Idiots. The cars that were level with where my car had been began blinking weakly as the water rose past their windows. So that’s what those far off car alarms were. (I was feeling very smug about having moved my car now.)

I went back out onto the porch and another step had disappeared into the murk. The water was now lapping against the door, but still was not in. The supposed crest was 1.5 hours past. Surely, this was it.

I went back inside and reality sank in as I noticed an inch of water flowing out from the bedroom into the den. Maple, the cat, was sitting on the floor sofa, looking concerned.

I called Gehrig and frantically explained something that is hard to understand if you’re not experiencing it: “The water is in the house, what do I do?” How was I going to pick everything up off the floor before it got wet?

It still had not occurred to me that I was in danger, or that there was more water to come. I was focused on picking up my “stuff.” I thought briefly about trying to mop the floor. I tried to find my wallet to no avail. Quickly, I grabbed the cat carrier, thank goodness it was close by and not thrown randomly in a closet, under the bed or left in the car as it normally would be. I scooped up Maple and she went into the carrier without a fight. Another first. Then, I frantically tried to prioritize. Move the laptop to the desk. Move the acoustic guitar to the couch. Pick up one box of records. The other is too heavy. The buzzer blows when I realize there is suddenly 4 inches of water throughout the whole house, seeping up through the floors from the basement. And then I saw the power strips. Glowing red from below an inch of brown water. I realize now that the house is unsafe. I could be electrocuted.

That’s how I wound up on the futon on the front porch with Maple, a coat, and my phone. No shoes on my feet, but thankfully, glasses on my face.

As I sat on the porch, unsure of my next steps. I tried to text my upstairs neighbor, but he was fast asleep. None the wiser. Next, I checked my renter’s insurance policy. Funny where your mind goes in times of crisis. My stuff. Not covered for floods. Of course. Still, I thought, it’s only 4 inches of water. Everything up high will be fine.

I noticed men in rafts cruising up and down the street. Their manner was calm, polite, normal. Courteously, they called out questions to the residents of my neighborhood: “Would you like a ride?” “No, thank you.” “Yes, please.” Nothing about these conversations indicated an emergency. I waited to be asked for several minutes, but no one seemed to notice me. Unsure of protocol but really wanting help, I meekly called out to one of the boats: “Excuse me.” No response. “Excuse me?” Again nothing. “Excuse me, sir!”

“Would you like a ride?”

“Yes, please, my house is flooded.”

It felt like hailing a cab.

By now, the water had risen to just under the cushion of the futon, making it so easy for my rescuers to paddle right up onto the porch. Once my uncommonly quiet cat and I were situated in the boat, I was able to take more pictures. We coasted past my car, still high and dry at 4 am. We stopped to pick up a few more passengers before arriving at the edge of the waterline. This was the end of the ride. No further instructions.

Barefoot in downtown Johnson, I texted a neighbor I didn’t know too well hoping she’d have an idea of where to go next. Fortunately, she was already up at Vermont State College’s Johnson campus with other evacuees. She drove down to get me and brought me to the impromptu shelter.

“It was as if all this water, filthy though it was, had washed away the norms that keep us isolated and separated from each other. ”

At this time of year, the northern skies start to fill with light before 5 am. Day was breaking as I arrived on campus. Things were even brighter inside the fluorescent-lit gym, which had been set up with mattresses from empty dorm rooms. I set Maple next to the bed offered to me and then went in search of a charger. The red battery indicator on my phone meant I would soon be cut off from communication and information, something I really wanted to avoid. I went from bed-to-bed asking to borrow a phone charger. Someone came through. Once I plugged in, there was nothing else to do but chat with other folks displaced from their homes, accompanied by pets and awake before dawn. This is how I got to know the people in my town.

The Response

The immediate, improvised emergency response was amazing: efficient, effective, and so full of care. Upon arriving at the gym I was given water, information and allowed to bring my pet (which I learned from others was a real improvement on the “no pets” rule that was abandoned moments before). Within an hour, some local women came bed-to-bed asking if anyone needed anything. I ordered a phone charger and cat litter, just as I would at a restaurant. Within the next hour we were informed that anyone with children or pets would be moved to a private room in a dorm. There were three hot meals a day provided by local volunteers. The local garden store donated high end outdoor equipment – Darn Tough and Smartwool socks, Hydroflasks, Blundstones, Timberlands, Merrells and Sorel boots. Being in the shelter felt luxurious. I was better taken care of than when in my own charge.

The next day, my friend and I drove down to the part of town that was still largely underwater. Everyone in town was milling around in boats, galoshes and waders to marvel at the extent of the flooding. The air smelled strongly of propane. The brown standing water was covered in a thin rainbow sheen of oil. Bubbles gurgled up to the surface. Reality started to sink in – this wasn’t just going to be a few inches of water on the floor. Because I could not get close enough to check on my car, I held onto the hope that I moved it just far enough for it to be spared.

The scene was grim, but the energy was not. Everyone was talking, commiserating, offering help, trading stories. I felt included, at home. It felt like summer camp – a space with no rules. We were in charge of ourselves. Neighbors offered each other canoe rides to assess the extent of the damage at their otherwise inaccessible homes and cars. Several people came right up to me to ask how I was doing, offering their homes, their cars and their hands to help. It was as if all this water, filthy though it was, had washed away the norms that keep us isolated and separated from each other.

The water receded quickly. By late afternoon, I was able to wade ankle deep to my car and apartment. Even from a distance, my heart sank. My electric key fob elicited no flashing tail lights and friendly beep-beep. I unlocked the car door manually and found water pooled in the cupholders. No dice.

The marshy front yard squelched beneath my feet as I approached my house. The futon was askew. It did not bode well. Nothing in my life had prepared me for what I saw as I peered into the living room. I was shocked by the extent of the wreckage. Everything was mixed together and smashed up, in different rooms. The bookshelves had collapsed. The furniture tipped over. The fridge was on its back. It looked like all my belongings had come to life and collapsed after a night of animated debauchery.

We later found evidence on the wall that the water had reached 3 feet high. Still, a few things were just like I left them, which was itself eerie and perplexing. I briefly marveled at the difference between the danger of the situation and the calm of my demeanor as the water rose. But even as I considered this, it felt abstract, other – I couldn’t yet find myself in this mess.

I didn’t even react. I was having fun at camp with my new friends. This was not a real problem.

I walked barefoot through the slippery muck that had once been my home. (I stepped on a rusty screw and later went to the ER for a tetanus shot.) As I looked around at my ruined material life, I wondered: How would I decide what to salvage and what to discard? How would I dry it, clean it, move it and store it? Discernment and decision making felt impossible. I had been stripped of my autonomy.

So I just grabbed a few essentials that had survived. Laptop, wallet, some toiletries. And I left.

There was nothing else to do yet.

Back at the shelter everyone was excited and relieved when we were informed that FEMA and the Red Cross had arrived, although it was unclear why. The local response had been so excellent, intimate, and caring. Perhaps we thought that the resources of a federal agency and national charity would make things even better. Not so.

The next morning, I heard from other flood victims that Red Cross would be moving everyone in dorm rooms back into the gym. The cushiony dorm mattresses were replaced by hard industrial cots. The huge food spread and donated clothes and shoes were gone. When asked, the officials confirmed the rumors. When I pressed for a reason, they said those were “the rules.” When I inquired about pets, I was told strictly that animals would not be allowed in the gym, but someone would come “deal with them.” Rehouse them. Remove the one comfort from people who had lost everything.

In the midst of all this, there were warnings that the town might flood again, that the water supply would be compromised. I was forced to choose between two unappealing options: On the one hand, with further wet weather, I could become isolated, cut off from supply chains, and subject to a new, opaque set of “rules” imposed by outside aid. On the other, I could leave, but I would be abandoning my new community, severing connections with friends, and eliminating the possibility of returning to deal with my wrecked apartment any time soon. I decided to stay. But then we were expelled from the dorms.

I was lucky enough to have a support network of friends and family and friends of friends of family. I had somewhere else to go and people willing to brave the blown-out roads to retrieve me. Others were not so lucky. I met a woman and her adult daughter in the gym. They had previously lived in a farmhouse on 13 acres. They had lost their home after being swindled into a predatory loan and had been forced to move into a tiny two bedroom apartment not long before the flood. The flood waters destroyed all they had left. And now they were removed from the dorm room and separated from their pets. My heart ached as I left them behind.

The Clean-Up

Once Gehrig returned with his car, we began the process of cleaning up. We labored under smoke-filled skies, in conditions “unhealthy for sensitive groups,” and under threat of more thunderstorms and flooding. It was extremely difficult to sort what was totally ruined from what might be worth trying to salvage. We tried to discern what would be easy to replace from what was precious – but when everything gets mixed up in the muck, your feelings get muddied, too. We didn’t know what to mourn.

For a while, I found it easy to disassociate from my own losses. Family photos turned to mush, ruined art supplies, and my own hand crafts were all just things that needed to be sorted. I was completely consumed with the purposeful task before me. The more practical things with less hope of rehab and less sentimental value were easy to throw away. Especially because we weren’t sure what could be safely salvaged. For example, I was inclined to bleach my sewer-smelling shoes, but would that have been safe and sanitary? We erred on the side of caution, not wanting a flood to be followed by a plague.

Because we didn’t have flood insurance, we were relatively confident that FEMA would give us a sizable grant to replace damaged ordinary things. It became a running joke: Uncle Fema is going to buy us new clothes, a new couch, a new TV. The FEMA inspectors that came certainly gave us that impression. Only after finishing the clean up did we learn that FEMA offers the assistance in the form of a low interest loan. Maybe we would have spent more than $70 in laundry quarters if we had known that.

Everything we were trying to salvage on the porches drying, protected from imminent rain. I was worried that if it flooded again everything on the porch would be whisked away. But, if we left it inside it could mold.

I was keenly aware that we were generating an immense amount of waste. And I felt so guilty about it. Because my job focuses on environmental crises, I know there is no “away.” Maybe I shouldn’t have owned it in the first place. I wondered how the waste removal industry would be affected. How does Casella handle its logistical operations when everyone in the state throws away everything they own in a single day? Could Vermont’s already overburdened landfill handle all of this?

At the same time, there was also a strange ease in being temporarily relieved of the ordinary environmental consumer dilemma. My daily practice of trying to discern the number in the triangle on the plastic clamshell was no longer relevant. Everything goes to the dump. The trash, the recycling, the walls, clothes, heirlooms. Everything. Aerosol disinfectant spray mingled with wildfire smoke, lingering propane, and probably a good deal of lead paint, fiberglass and asbestos. It all formed a toxic cocktail shroud over the emotional loss. I darkly quipped, “Today is the day we get cancer.”

The clean up process took about a week. Each morning began with a fresh news report on some coinciding environmental catastrophe. We were not alone. People in Kentucky were losing their homes to flooding too. People in Arizona were dying from heat stroke. People in Oregon were fighting fires. Climate chaos contributing to localized collapses everywhere.

Nevertheless, the atmosphere in Johnson was still somehow and in some ways better than before. People were milling around town, giving out free food to anyone that wanted some. I considered how idyllic this life was. A perfect utopian town. Everyone caring for each other, engaging in fundamentally meaningful work. Working for themselves, providing for each other. The food and help was free – not means tested. Everyone was in a perfect state of flow, and their needs were all taken care of. People were smiling on the bright sides of the catastrophe, wrapped in silver linings. I was having too much fun. “Have you cried yet?” my father asked over the phone. Why should I, I thought, I live in a perfect society now.

Towards the end of our clean up, Gehrig accepted a last minute gig in Middlebury as a sub for a drummer that got COVID (more coinciding crises). Why not continue to make friends, put yourself out there and feel normal even when your drums are waterlogged and molding? Sure, the logistics of getting him there added a layer of stress and compounded into a series of avoidable mistakes, including lost drumsticks and risking a speeding ticket. But Middlebury is nice. It is cute. It might be nice to spend an evening there.

But as we traveled through the Champlain Valley, the wool quickly came off my eyes. So many nice towns – cute and aesthetically appealing, with dreamy boutiques and cafes and promenades. Even after the rain fell, you could still tell the rich and exclusive places from the poor and neglected ones.

The upscale jazzy restaurant didn’t offer any dishes under $20. I couldn’t justify paying so much for a single meal while mentally tallying the losses I’d endured. Everyone around me seemed blissfully unaware or unconcerned with the total losses sustained by people with so much less just dozens of miles away. I struggled hard as Gehrig performed, feeling so distant from everyone in the same room. I know that life goes on, but when it’s your life that’s been upended, it is hard not to feel left behind. I thought of companions in the shelter. The people that lost everything were the ones that had so little to begin with. The social safety net only came out after the fact. How could I reconcile the fact that displaced seniors who didn’t even have all their teeth were coexisting in a state that is rapidly becoming dominated by resorts and 2nd and 3rd homes for the super-rich? Why should I have to try to make sense of this?

I thought about how easy it is to avoid the dissonance and disparity – especially in a built environment that allows us to stay separate. In the ordinary course, Vermonters drive their private vehicles to the places they want or need to go. We are both car-dependent and car-divided. I had lost my car in the flood, but fortunately our household had another that happened to be at a safe distance. Neighbors who were not so lucky had to rely on the free shuttle – set up only in the aftermath and that would surely be gone before long – to get to stores and medical care in Morrisville. I’ve always been baffled by the lack of public transit infrastructure in rural places, but now my rage at the imprudent use of the rail trail for recreation was lit up. Rather than empowering rural communities to access good jobs and good food, without having to afford, purchase, and maintain individual fossil fuel machines, Vermont had chosen to create yet another playground for those with leisure time. There had already been train tracks.

Later, in quiet moments, we were forced to grapple with our own losses, which we estimated to total about $30,000. It’s almost automatic to shrug it off as “just stuff.” In fact, it’s a little appealing to do so because I really want to be a non-materialist. My life is not defined by how much I have, but by my relationships and how I spend my time. So, it’s not surprising that so many of the things we lost were gifted, found, or made. Replacing these things would require spending a lot more money than they are objectively “worth.” Giving up on them requires me to divest from the meaning they held.

Moreover, without some of our things, the options for how we might spend our time or connect with our friends also narrowed. As Gehrig and I started to look ahead, we kept bumping into the losses: “Oh, that’s right. We can’t go camping next month. We don’t have a tent anymore. Or any other gear.” To add insult to injury, we have to face the fact that some of our losses were caused by exhaustion. At points of overwhelm, we threw things out with abandon so we could get through the clean-up sooner. It is easy to get caught up wondering about what things we might have saved – and what possible experiences might still be open to us – if we’d had the mental wherewithal to try rehabilitating more of our belongings.

I also think of the hours I had to work to build up my collection “stuff” and what it would take – in terms of labor time converted to earnings – to try to rebuild it. In a time of collapse from all angles – fire, flood, economy – what am I working towards? What am I saving for? If who we are and what our lives amount to are defined by how we spend our time and who we have relationships with, shouldn’t I try to limit how much of my time I trade for money and stuff?

Now as I try to take a new approach to consumption I can’t help but ask myself, is this going to be worth cleaning up when the next disaster hits? Cleanup from the flood would have been much easier and less heart wrenching if I had just had less stuff to begin with. Would I spare myself the guilt of creating more waste when it is destroyed again, or when I leave this world? Does the adage “it is better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all” apply to material possessions? Or is less more?

These questions were already on my mind before the flood. I had been feeling full. Feeling like I mostly had what I needed and wanted. I had home, a car, and had compiled a pretty sweet crafting center, replete with loom, spinning wheel, sewing machine, and stained glass equipment.I honestly could not think of what to add to my Christmas wish list. Had I won Capitalism?, I wondered. Could I opt out of working so much and instead use the time to enjoy the stuff I had acquired? I had project plans piling up and recipes books I had never cracked open. The only thing I didn’t have enough of was time. If I was intentional about valuing my time and balancing its use to earn and to live, I might be able to actually enjoy what I had. Time had become more valuable to me than money. I felt compelled to work just enough to cover my basic ongoing expenses, enjoy the rest of life, and – because there was not much more I wanted to buy – save for a modest house.

As a child, my parents were separated and always moving around. I never lived in a home for longer than 3 years. As an adult, the one thing I have been aspiring for has been to put down roots, form a community and make a home. In fact, all my artistic aspirations have been oriented toward one day improving a home: learning to make tiles and grout for my eventual bathroom and stained glass for my windows. Sewing my own curtains, weaving my own rugs. As a Zillenial, the home ownership aspiration is feeling less and less achievable. To get a mortgage means locking in a higher monthly housing rate for 30 years, and as such having to work so much that I might not be able to enjoy it. So I’ve also wondered whether it would be better to continue renting, work as little as possible, and live in the present instead? Hard to tell.

But in a matter of hours, everything changed. It is all gone. All that I saved for, all that I spent, all that I made, and all that I found. I was so close to having nothing to save for but a house, or nothing to work for but my everyday expenses. Now there is so much that I need. And the wish list is long, too. I got swirled around in the flood and pointed back in the direction of consumerism. But as I make lists of what I ought to replace, the questions stream in:

-

Is it worth the money – the time – needed to get things back?

-

Can I love the process of art without the promise of keeping what I create?

-

Does that make any sense as these types of climate catastrophes become more common and insurance becomes ever more expensive and less effectual?

-

Will something similar just happen again?

-

Am I supposed to keep everything in the loathsome plastic?

-

Put everything dear to me on high shelves?

-

But what if the next disaster is a fire?

-

Should I let my stuff collapse and degrow?

-

Is this the moment to commit to being an ascetic minimalist?

-

How do you prepare for everything at once?

-

How do you come out of this stronger and wiser?

-

Does everything have to be a learning opportunity or can it just be a random thing that happened?

I don’t have answers to these questions yet, but I am sure of one thing: my last bit of faith in the American Dream receded with the flood waters. And it’s not retrievable.

We never got to say goodbye to our home. So, we also lost the closure that comes with deciding to move on one’s own terms, the bittersweet excitement that comes from packing up boxes and saying one final goodbye to a place you called home for however long. We never got to close the loop and see the place returned to the state we found it in and locked up for the last time. Even with all its imperfections, that little apartment in Johnson was our home. It was an animated, cozy, hygge space with a life and energy distinct from all other places we had lived. And now, as it is gutted, so are we.

I’ve been stripped of more than stuff, money, or even closure, but of my very identity. It’s hard to feel ambitious or hopeful for the future or know how to best focus my efforts, hopes and dreams when it can be taken away from you and everyone around you without any regard for the memories and struggles made to get there. And without any compensation from any sort of social safety net. Someone told me recently that hope is a muscle that needs to be exercised. It’s not just a feeling of faith that you get to keep and have. You aren’t just a hopeful person or not. You have to practice. But I don’t know what to want. I don’t know what to hope for.

I used to live in a kind of karmic fear. I worried that my life hadn’t been random, tragic or hard enough. I sensed that something terrible must be coming. So when the flood happened, I felt almost relieved. Perhaps I had paid my cosmic dues, and all would be fine from here on out. And I feel a certain amount of guilt, too. I have so much more than other people. I lost less. I have a better chance of bouncing back, I have a strong network and relationships beyond the places of worst impact. Maybe I’m not really a victim. Maybe I don’t really deserve help. After all, it could be worse.

Despite my focus on the material losses, I do realize how lucky I am. At first, I never really felt I was in danger. There was never an alarm or an evacuation order – nothing to signal urgency. I felt dumb for not being better prepared, for not picking more items off the ground. But it later dawned on me that had I been a heavier sleeper, I may have woken up with the water rushing around my bed, all charged with electricity, phone dead, and appliances crashing down around me. With no way to call for help. Who knows what could have happened to Maple. The alternative is terrifying. I remind myself over and over: I am lucky to be alive.

And being alive leaves me with the task of meaning making. I would have thought that surviving a disaster would snap me out of my slump, make me be grateful for all I have. It might have jolted me and caused me to focus on survival rather than ambition. I imagined I might get a sense of biblical meaning – a literal flood washing away the old me and giving rise to some new, better perspective. I was hoping for some kind of rebirth. I still want to be able to look back and say:. “And then the flood changed all that, and made me who I am today.” In the immediate aftermath, so much did change. Society suspended allowed full focus on the here and now. What mattered most were the people around me, the tasks in front of us. For a brief moment, it felt so good. But now, beyond that disruption of oppressive normalcy, I am left feeling stripped and confused. The absurdity of the modern world is all the more real.

“A new perspective doesn’t just happen after something like this. I suspect that processing it is what makes it happen, which is part of why I’ve written all this. ”

— Nissa Coit

One of my favorite books is Of Mice and Men, by John Steinbeck. (I love it so much that I even made a playlist with the same name full of songs about people having cute homes in the country. It’s the sonic equivalent of a vision board with a dark twist.) The poem that inspired Steinbeck’s title is about a mouse whose home and stores for the winter are accidentally destroyed by a horrified, well-meaning farmer, who can’t even apologize or help the mouse. If you haven’t read it, here’s the take-away: Sometimes random shit happens. Lennie just never gets his rabbits. Not because he didn’t deserve it. The book and my playlist (which I still have because it was virtual) both remind me that no matter what you do, how smart you are, or how well you prepare, the best laid plans of mice and men go oft awry.

Steinbeck’s original title for the book was simply: “Something That Happened.” There was no cosmic or karmic meaning behind it. Pure Sisyphean absurdity, and no matter how much you want the world to have meaning, sometimes it just doesn’t. Bad stuff happens to good people, and vice versa. As one of my neighbors – a man who lost the home he raised his kids and grandkids in – said, we had “bad luck and good karma.”

The flood happened. I am here. Things will keep happening.

All we have is now.

Now you are turned out, for all your trouble,

Without house or holding,

To endure the winter’s sleety dribble,

And hoar-frost cold.

But little Mouse, you are not alone,

In proving foresight may be vain:

The best laid schemes of mice and men

Go often awry,

And leave us nothing but grief and pain,

For promised joy!

Still you are blessed, compared with me!

The present only touches you:

But oh! I backward cast my eye,

On prospects dreary!

And forward, though I cannot see,

I guess and fear!

– Robert Burns, To a Mouse