“Didn’t I JUST go grocery shopping LAST week? Are you telling me I have to do it again ALREADY?” I find myself getting frustrated by the general ongoing maintenance of the little creature I have to keep alive, called Nissa. When will I just be DONE, and allowed to do the things I want to do, like knitting and baking, gardening, volunteering, and just walking around? Not just hobbies, but life-giving, alternate future-building activities. To just live into the real world, real life, the magic of the world I know is there but I don’t have time to access? How has it come to be that we now have two jobs – the real-life work to keep ourselves, our families, and our communities kept, and the other one we have to do on top of that, to afford to keep ourselves, our families, and our communities kept?

Yet, the dust keeps falling, so I’ll keep having to dust.

I keep eating the food, so I’ll keep having to go grocery shopping.

Compartmentalizing the work I do to keep myself alive, the work I do for wages, and the work I do for enjoyment and relaxation made it feel that the former two were something to get through, something maybe, if I worked extra hard, I would one day have glorious Nothing to do, and I could fill it with tinkering and puttering, and silliness, and play and magic and spontaneity. Obviously, this is an absurd arrangement. And yet, as a young adult, this was my mentality, and perhaps the mentality of many of us in the working force: grind for the weekend, grind for vacation, grind for retirement. The fact that my aspirational version of “retirement” looked like getting off grid, opting out of the market, and building a commune – all of which takes its own kind of work – only made the logic more laughable.

As I became more aware of the collapsing complexity around us, though, not everything was squaring up. I recognized that the future wouldn’t look the way I once thought it might. A common experience I have heard from those that descend the path to becoming collapse-aware is a sense of despair and grief for the future opportunities that are promised us by the conventional narrative of the American dream under capitalism. Even if intuitively we understand that infinite growth is impossible, that there are finite material resources, and that there is no real concerted effort to mitigate the effects of climate change on our societies, many still internalize the imperative to achieve material comfort through academic or professional ambition, to save for retirement, to invest early, to buy a house, to pull a homestead up by its bootstraps. Even those of us that have not totally bought into this tale still feel a sense of loss when we embrace the inevitably of catabolic collapse, for better or worse. It’s hard for us to reject techno-optimism, or even our own responsibility to be the generation that changes it by working hard in our careers.

Unlike prior generations, mine is disillusioned with the work-for-money paradigm. Whereas a single income could once support a family, afford a house, healthcare, education, and a pretty good shot at regular vacations and a comfortable retirement, now even couples – double income no kids (or, DINKs as the kids say) – are struggling to make ends meet, let alone have any leisure or security to look forward to. (And no, it’s not just a phase, mom.) Millennials, and all generations that follow, are stuck on this endless hamster wheel to nowhere. This leads to an understandable epidemic of burnout, depression, anxiety, and loneliness. If money can no longer guarantee a happy, safe and secure future, the way it once did, why should we be motivated to trade our time for wages, put real life off for some uncertain and possibly unlivable future?

Before, the message was if you can’t make money at knitting and gardening as quickly as a machine, then it’s not worth doing – an impractical use of time. But if we can’t actually rely upon an endless stream of trans-oceanic shipping containers, well-stocked stores, and just-in-time supplies of affordable goods, being able to clothe and feed yourself starts to seem pretty smart. Acknowledging collapse offered relief –maybe the things I’d rather be doing actually were the most practical things of all. And not just the activities that involved material culture – also socializing. Even “just” making and hanging out with friends – creating the caring connections that create resilience – was well worth my time. Any remaining conventional achievement and career ambition I had was redirected with renewed vigor to building a commune, buying a homestead, building resilience and community as quickly as possible. I was motivated to strategically invest in this alternative future with as much intensity as an investment broker would invest in the stock market.

Achieving a flow state at the pottery or spinning wheel, or while inventing some jig, pulling weeds in the garden, the focused fervor that would come over me had a sort of ambitious desperation to it. If I work really hard now and achieve something in my career, maybe I will one day not have to work so much, and I can just be as happy as I am right now. How perverse to be sitting and doing something so joyful, and ruin the moment with the worry that you may not ever be able to only do that task without worrying about Other Things.

Before the floods, I had an aching fear that efforts to work hard for some future homestead would be in vain. The floods only proved this point to me. Retrospectively, thinking of the dread at the uncertainty of the future that Of Mice and Men shook within me, I realize how wildly I had missed the point of this book. While I understood that planning too far into the future can be a source of perpetual torture, I did not fully internalize how to change my habits and perspective in the face of this wisdom. I was still stuck in a middle zone, clinging to the idea that maybe I could work my way out. I was not at all sure how to take the leap into some other way of living. Statistically staring down the barrel of 40 years of full-time work, endless chores, and a few precious outlier moments of human connection and pursuits of passion projects made it hard to move toward an alternative, no matter how much I wanted one. In the looming shadow of collapse and in the vivid glow of what I wanted the world to be, the day to day began to feel insurmountably Sisyphean.

Caught in between two world views, I began scouring the web for answers. My search history includes some niche entries like, “how do people deal with the absurd, in the face of collapse.”

That’s how I stumbled upon Camus’s advice to find joy in the everyday rolling of the rock up the hill.

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Seriously? That’s it? Then why start rolling up at all? Why not just build a picnic at the bottom of the hill and lean on the boulder?

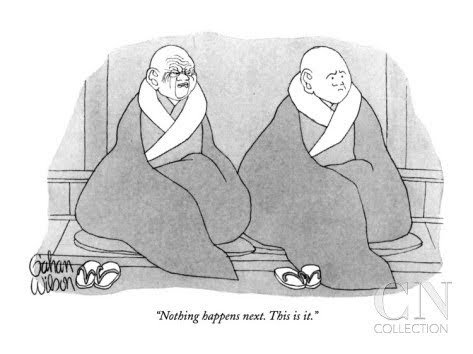

Camus wasn’t alone in this view. Other writers, those living now, grappling with polycrises, acknowledging collapse, that have found peace, and joy arrived at similar conclusions.. Enjoy the Now. Be mindful. Buddhism. Easier said than done though, isn’t it?

Mindfulness usually leads to recommendations about building a meditation practice. Been there, tried that. But it has never seemed to “work” for me. There was never transcendence. I never found my way into the beyond headspace. It certainly did not make the everyday struggles of coping with collapse, and work feel any better.

But maybe the problem doesn’t lie with meditation or with me. Maybe meditation, like just about everything else, has been instrumentalized. Approaching meditation as a “solution” undermines the endeavor from the beginning. Meditating for a desired outcome – whether it is to be more productive, creative, calm, or content misses the point. Perhaps that is a positive side effect, but it deforms the process to only be in service to a goal.

Fortunately, while I was frustrated with meditation recommendations, I came across some insights about attention that made me believe it just might be possible for Nissyphus to get happy about the boulder. Neuroscience tells us that the focus of your attention is like a spotlight, that you can point anywhere you like. And you can point it at up to 2 things at a time. Humans are really not good at multitasking. We may feel that we can, but actually, we are task switching. Even computers cannot multitask. They can just switch tasks very, very quickly. So, if you decide to direct your “spotlight” of focus on something, the focus on whatever else is claiming your attention will disappear.

This is true even for, you guessed it, meditation masters. CT scans of their brains reveal the same spotlight, the same tendency toward distraction… and a much greater ability to quickly refocus. The takeaway: you will not ever fail or succeed at meditation. You will never “arrive.” You will only get faster at refocusing. So, whenever your mind wanders, just bring it back. How often I would glance at my happy cat, lounging, totally in the present, without a care in the world, and wish “ah I wish I could just be a cat.” Just, for a moment, try to focus your spotlight on feeling like and embodying a cat basking in the sun, and be present!

In his book, Wherever You Go, There You Are: Mindfulness Meditation in Everyday Life Jon Kabat-Zinn says “Ordinarily when we undertake something, it is only natural to expect a desirable outcome for our efforts…Meditation is the only intentional, systematic human activity which at bottom is about not trying to improve yourself or get anywhere else, but simply to realize where you already are… When we understand ‘this is it,’ it allows us to let go of the past and the future and wake up to what we are now, in this moment.”

sqs-block-image-figure intrinsic ” style=”max-width: 473px;”>

Kabat-Zinn goes on to quote transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau: “In eternity, there is indeed something true and sublime. But all these times and places and occasions are now and here. God himself culminates in the present moment, and will never be more divine in the lapse of all the ages.”

This made me reframe the task. I simply needed to reframe my relationship to the present moment. Again and again. Doing so might allow me to exist in the collapsing world and appreciate its bits and pieces as the material from which I and others would start making the next.

I tried this very approach while writing this piece. Had you observed me during, you wouldn’t have described my actions as work-like. I mostly didn’t sit at a desk or stare at my computer. Rather, it was created sitting, staring out the window, chopping vegetables with a blank mind, and letting my ideas flow, coming to me. When I thought of something good, I would pop it on a sticky note, and go back to what I was doing. The thoughts moving through the living.

Filmmaker, David Lynch, says of creative ideas: “I think they exist like fish. And I believe that if you sit quietly, like you’re fishing, you will catch ideas.” Sometimes, the best ideas and best creativity come out of rest and joy and not “working”. Or, maybe if our work was our own, and leisure and work were united as a whole Life, if time was not enclosed and commodified, it would be easier to enjoy life and face the absurd. So, I guess, Sisyphus could be happy, if he studied the intricate inclusions on the boulder, didn’t think too hard about what he was going to do after he was done, and appreciated the exercise he was getting and the endorphins that get released from it.

Thoreau says: “There were times when I could not afford to sacrifice the bloom of the present moment to any work, whether of the head or hand. I love a broad margin to my life. Sometimes… I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in reverie, amidst the pines and hickories and sumachs, in undisturbed solitude and stillness, while the birds sang around or flitted noiseless through the house, until by the sun falling on my west window, or the noise of some traveler’s wagon on the distant highway, I was reminded of the passage of time.”

Once, when I was practicing this new outlook, I tried (‘try’ being the key word here) to focus wholly on making dinner, to savor the task and the fun and creativity of it. I tried to let go of my goal of achieving the perfect end dish by following the recipe to a T. I tried not to rush through it to get on with the actual fun leisure activities. I swayed and danced a little, and munched happily on a miniature watermelon as I dashed in a bit of this and a bit of that. I observed the sweet crunch of the fleshy rind of the watermelon, mixing with the aromatic spices in the sizzling pan. In the space that would normally be taken up by a running list of overwhelming to-do list items I wanted to get through after dinner, I was inspired to put some slices of watermelon into the dal I was making. It was delicious. Enchanting, even.

And that’s when I realized that it wasn’t the labor I resented, but it’s utter lack of luster. It wasn’t the doing, it was the dullness. I didn’t need to get through tasks or empty my mind. I needed to be present in my own life. Playfully or purposefully – just by being present, I could make mundane moments feel like magic.

In 2022, a Belgian feminist film from 1975, titled Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, was crowned the greatest film of all time, by Sight and Sound. The 3+ hour movie captures the power of a deliberate tranceline cadence of mindfulness to make ritual magic of the mundane. It elevates the mundane to something beautiful, worthy of the silver screen.

Much of the film is like this clip. It invites you to fully notice real life, and reminds you that THIS is how long LIFE takes. 3+ hours is necessary to completely engross you in the meditative ritual of everyday life. It makes you pay attention to the often overlooked or invisibilized, unpaid “women’s work” upon which capitalism depends. It defies a dominant culture that exhorts us to speed things up. It reminds us that we are not meant to cram as many tasks into an hour as we can, to then move on to the thing we would rather be doing. Life passes us by when we perceive it as toil marked by a few minority moments of happiness and joy.

All this got me wondering: if mindfulness could enliven and enchant the everyday, what would happen if I stepped things up a bit and brought some ritual into my life…

According to the Britannica, ritual can be defined as “a formal ceremony or series of acts that is always performed in the same way.” Humans need ritual. We have evolved to need it. In fact, some even theorize that ritual allowed the transfer of knowledge in pre-linguistic human societies and set us on a path to being a highly social species. In the article How Ritual Created Human Society, Dimitris Xygalatas paraphrases French sociologist, Emile Durkheim, saying of the two phases of aboriginal life:

“These two different phases…constitute two very different realms: the sacred and the profane. The profane includes all those ordinary, mundane, and monotonous activities of everyday existence: laboring, procuring food, and going about one’s daily life. In contrast, the realm of the sacred, which is created through ritual, is dedicated to those things that are deemed special. The performance of collective ceremonies allowed people to set their everyday worries aside and be transported, albeit temporarily, to a different state.”

Ritual may even be what allowed us to evolve into the beings capable of having such complex crumbling social systems to begin with, and what might allow us to go even further into eusociality, true sociality, the way of being together for the greater good, like bees and ants. Xygalatas further explains that neuroscientist Merlin Donald sees ritual as “a mental foundation stone for the evolution of social cognition, allowing early hominids to align their minds with social conventions.” For Donald (as expressed by Xygalatas), “[b]y establishing a shared system of collective experiences and symbolic meanings, ritual helped to coordinate thought and memory, allowing a group of humans to function as a single organism.”

Rituals often arise and are maintained out of a desire, or a necessity to make sense of or keep track of real circumstances. To connect with others, to cope with uncertainty, to mark the passing of time with something special, and memorable. To connect with the divine, or nature, or other people, or whatever it is to you that is bigger than yourself. Perhaps ritual is just the thing we need to revive in order to create new social organizations, to advance to a more eusocial way of being together. Maybe we can take care of ourselves by taking care of each other. Prioritizing the next generation as much, if not more than, our own.

If only it were easy to re-ritualize our lives. Unfortunately, the kinds of connections that are consonant with ritual can be hard for people living in societies of secular individualism to make and maintain. Most of us lack access to the very things that rituals spring from: connection to place and land, shared history, and seasonal shifts, as well as other people who also have and cherish access to all of the above. Few of us enjoy a continuous, uninterrupted line to ancestral ritual practices. Under these circumstances, we spend time, energy, and sometimes money trying to find ways to connect that feel meaningful, square with our values, and are consonant with what we accept to be true about the world, as supported by some evidence.

This search raises a big question: How can we create shared rituals that feel neither arbitrary nor appropriative? Dance, craft, crystals, astrology, tarot – while each of these practices can provide a break from the everyday, they often feel more “good enough” than “right” or “satisfying.” As we begin to establish our own personal everyday rituals, to connect with something that feels more right by re-enchanting the things we know to be real and important, we can then begin to share these practices with larger and larger friend groups, melding what is meaningful to each of us together into something strong. If it matters to you, dear one, it matters to me too.

Until then, can we work on merging the sacred and profane? What if we no longer compartmentalized work, leisure, and life, and the divine? What if we allowed them to exist in a spectral arrangement, a layered configuration. What if we could live simultaneously in the dystopian present and the utopian future?

When I find myself feeling overwhelmed by the state of the world, uncertain personal and collective futures, things not within my power to change, or sad that instead of doing art, dancing around a fire with my tribe, spending time with friends and family, I have to instead work for a wage, shop for insurance, or go to the grocery store, I breathe and try to focus my spotlight on chopping a tomato, or vacuuming with my whole being. To appreciate the weird beauty that is the curated aisles of the grocery store (while still being critical of them). And be grateful that I am able to. And sometimes, magic and art and childlike creativity, and ceremony creeps in anyway. And I get to live real life in that moment.

You may create new, adaptable traditions and rituals, suited to your unique ecology – the time, the needs, and circumstance of you. The same way many rituals and traditions arose before. From scarcity, we create specialness and abundance. So, let’s piece together dinner from what we have. Lentils in the cupboard, and a watermelon you will likely forget about. You don’t want it to go bad, so you eat it now, in this moment, while you are thinking about it. You don’t need to save it for some grand event or special occasion, or perfect recipe. You eat it now, and in being present, you develop a grand tradition, a new recipe, that whenever you make it again, will mark the special magic of that first spark of inspiration. Changing worlds, means changing traditions and rituals. So, we need to clear space and open our minds to let them in. You don’t need to believe in anything, to appropriate anything, other than that humans exist as a part of nature, not separate from it, and that now is now, and all your life is made up of little moments of now. Better enjoy it while it lasts. Take the time to stare fully at your brethren, the sumacs and hickories and pines.

Let me end with an invocation not to add “ritual” or its even more exalted relative “ceremony” to your to-do list. If you do, you’ll wind up feeling guilty as your tarot cards or yoga mat collect dust and your desperation to finish your chores and work so you can get on with your real life grows. Instead, embrace everyday mindfulness. And refamiliarize yourself with ritual by devoting yourself momentarily to the small stuff. Get lost in the strangely spiritual magic of folding the laundry, chopping tomatoes, with your whole being and full attention. With only two spotlights of focus to work with, keeping one empty may allow your mind to open to some playful creativity that there would not have been space for if you had been mentally multitasking. Keep the door of your mind open, not to the “intrusive” thoughts, but maybe… surprise visitors that you greet with curiosity at the door. Let them make their case. As I did when I first compared the watermelon rind to squash, then observed that sweet juice and aromatic spices pair nicely together. Meet what comes, not with dismissive judgment, a goal-oriented “right way to do it” recipe, but with playful curiosity, delight.

Accept that if it turns out gross that’s OK, the journey was yours. It might even have been fun. It was part of life. Your life. And maybe accepting, embracing, and adding your own flair to a changing world can make your life as unexpectedly delicious and fun as watermelon dal.